Fear is one of the most primal human emotions, a visceral reaction that bypasses logic and self-awareness to grip our very core. In storytelling, fear and tension serve as key elements to not only entertain but to immerse the audience in a narrative experience that is both unsettling and captivating. Yet, creating fear and tension in writing isn’t about jump scares or sudden plot twists—it’s about psychological manipulation. Crafting fear is an art, one that requires precision, pacing, and an understanding of what unsettles us at the deepest level.

In this essay, we’ll dive into the mechanics of creating fear and tension, exploring not only what works on the surface but also how to exploit psychological cues and narrative structures to make a story truly chilling.

Understanding the Nature of Fear in Storytelling

Fear in storytelling works because it taps into our most basic survival instincts. We fear the unknown, the uncontrollable, the uncanny—things that subvert our understanding of reality. However, effective storytelling doesn’t just show us what to fear; it suggests fear, allows it to seep in slowly, almost unnoticed, until it takes hold.

Fear, at its essence, thrives on vulnerability. The best horror stories understand this and work to expose their characters’ (and, by extension, the audience’s) deepest vulnerabilities. Consider the quiet dread in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House or the creeping paranoia in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Both stories deal not with overt, physical threats but with the unsettling notion of losing control—over one’s own mind, one’s surroundings, one’s sense of reality. Fear is cultivated not by the threat itself but by the anticipation of threat.

When you’re crafting a story with the intent to frighten or disturb, it’s essential to remember this: Fear works best when it is unseen, when it is lurking at the edge of perception. The audience should feel as though something is wrong long before the characters are fully aware of it.

The Role of Tension: Keeping the Audience on Edge

Tension is the backbone of any successful horror narrative, but tension and fear are not the same. Tension is the sense of uncertainty, the tightening grip of anxiety that draws the reader forward, eager yet hesitant to see what comes next. While fear is an emotional response, tension is more mechanical—built up through pacing, structure, and the careful distribution of information.

The art of tension lies in its restraint. Too many writers, in their eagerness to shock or horrify, release the tension too early or too suddenly. This can be a fatal mistake. A story that reveals its hand too soon loses its power. Imagine a rubber band being pulled tighter and tighter—the longer the stretch, the more satisfying the eventual snap. A story should operate in much the same way, pulling the reader along through quiet moments of foreboding before unleashing its terror.

One way to build tension is by controlling the flow of information. Consider what you reveal to the audience and what you withhold. The less they know, the more they’ll fill in the gaps with their own anxieties. Alfred Hitchcock famously referred to this as the “bomb under the table” scenario. If two characters are having a conversation and a bomb suddenly goes off, the audience is shocked for a moment. But if the audience knows the bomb is under the table and watches the characters go on, oblivious to their impending doom, tension builds exponentially.

To heighten tension, the writer must play with pacing—slowing down at critical moments to prolong the unease. Short, clipped sentences work well in moments of action, but long, descriptive passages force the reader to linger in moments of suspense, making every heartbeat feel agonizingly long.

Exploiting the Uncanny: What We Fear Beyond the Physical

One of the most potent tools for generating fear in storytelling is the uncanny—the idea that something is both familiar and foreign at the same time. This is where the true psychological horror lies: in things that are almost normal but slightly off, slightly wrong. The uncanny makes us question the very fabric of reality.

H.P. Lovecraft, the master of cosmic horror, often toyed with the idea that the most frightening thing is the unknown, the unknowable. His stories frequently involve beings and forces that exist beyond human comprehension. This concept of “fear of the unknown” is crucial in creating horror that lingers long after the story has ended. The trick is to leave enough ambiguity that the audience is never entirely sure what they’re dealing with.

The uncanny works because it destabilizes our understanding of what’s real. A house that’s just a little too quiet, a person whose face seems familiar but isn’t quite right—these are details that disrupt our sense of normalcy. The more we try to rationalize them, the more uneasy we become.

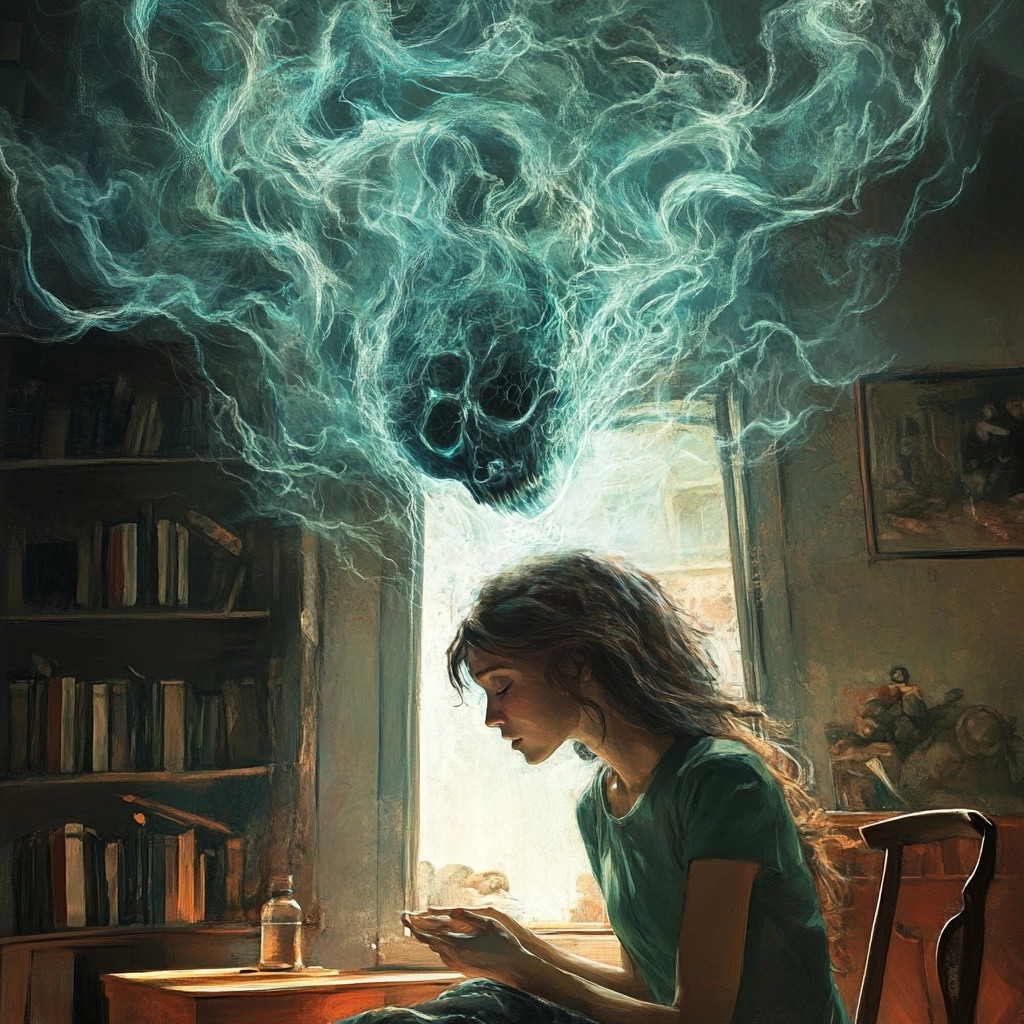

This is why ghost stories and tales of possession continue to resonate across cultures and generations. Ghosts are the embodiment of the uncanny—they are human yet not human, existing on the fringes of the physical world. They force us to confront the uncomfortable idea that death is not the final boundary, and that something may persist beyond, something we cannot control or understand.

The Psychological Impact of Isolation and Vulnerability

Isolation is another key element in generating fear. Whether physical isolation (a character trapped in a remote location) or emotional isolation (a character who feels alienated from those around them), cutting characters off from safety and comfort is a surefire way to make them (and the audience) feel vulnerable.

Think about films like The Shining, where a family is trapped in a snowbound hotel, or Alien, where a crew is isolated in the vast emptiness of space. These stories work because the characters have no means of escape, no one to turn to for help. In these situations, the environment itself becomes an antagonist, amplifying the sense of dread.

Isolation also plays on the human fear of abandonment. When we are alone, we are more vulnerable, more susceptible to whatever threats may lurk in the darkness. This vulnerability is essential in creating psychological horror. The audience must feel the characters’ isolation deeply, imagining themselves in that same helpless position.

The Slow Descent Into Madness

Fear is not always external. Some of the most compelling horror comes from within, from the mind unraveling under the weight of stress, fear, or supernatural influence. This is the essence of psychological horror: the terror of losing one’s grip on reality.

Stories of madness work so well because they mirror a very real fear we all have—that we are not as in control of our minds as we think. In stories like The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, we see a protagonist slowly losing touch with reality, her perceptions becoming unreliable. The reader is left to question what is real and what is imagined, adding another layer of tension.

The key to writing a successful descent into madness is to make it gradual. The character should start off with small doubts, small lapses in logic or perception, before spiraling into full-blown paranoia or delusion. The reader should be dragged along for the ride, unsure of what to believe, caught in the same web of uncertainty as the protagonist.

Conclusion: Mastering the Art of Fear and Tension

To create fear and tension in storytelling is to play with the audience’s emotions, to manipulate their expectations and their sense of safety. It’s about understanding what makes people uncomfortable and stretching that discomfort out until it becomes unbearable.

Fear thrives on the unknown, the unseen, and the uncanny. It’s about making the audience question what they think they know, keeping them on edge with carefully controlled pacing and an unrelenting sense of vulnerability. Tension, meanwhile, is the string that pulls them through the narrative, tightening with each new revelation, each moment of uncertainty.

When fear and tension are wielded effectively, they create an immersive experience—one that lingers in the mind long after the story ends. It is this lingering sense of dread, this feeling that something is not quite right, that defines the most successful horror stories.

Leave a Reply